Why decompilation?

Why not just disassemble?

Consider the Java world, where there are simple disassemblers and sophisticated decompilers that often work well and with little user intervention. Would you use a Java disassembler to try to understand some Java bytecode program? Most likely not. If there is a good decompiler available, you don't need to see the individual instructions. If and when a good decompiler for executable programs becomes available, it will be a better choice than a disassembler in most circumstances.Applications

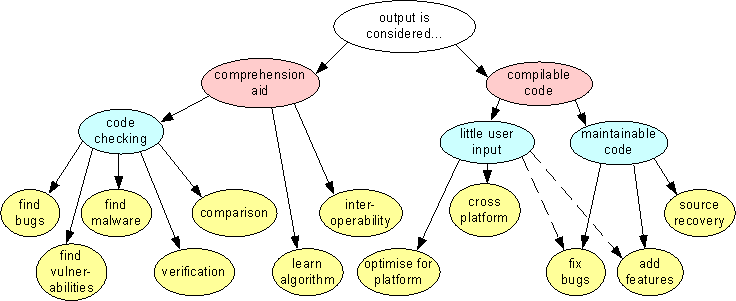

There are many reasons why you might want to decompile a program. Here are some of them, based on this diagram: If the output is considered...

If the output is considered...

- A comprehension aid. You don't have the resources to create compilable code. Even so, you can do these things:

- You can perform code checking of various kinds:

- Find bugs. You focus on the area of the program that you are interested in. looking for bugs.

- Find vulnerabilities. You scan the whole program, looking for code that could be exploited.

- Find malware. Again you scan the whole program, this time looking for code that has already been exploited. It may be easier and quicker to find malware in 1000 lines of C than in 10,000 lines of assembler.

- Verification. You want to make sure that the binary code that you have corresponds to the source code that you also have. This is important in safety critical applications.

- Comparison. Suppose you are accused of violating a software patent, or suspect that someone has violated your patent. You can show how different or similar two programs are by comparing decompiled source code. To some extent, a decompiler can make two different implementations of the same program reveal their similarities. As an example of this, using different optimisations with the same compiler somtimes results in similar decompiled code.

- Learn Algorithm. To the extent that is allowable by law, you might want to discover how a particular feature of a piece of software is implemented. It's a little bit like browsing patents online; you can't use what you see directly in a commercial setting, unless you have an arrangement with the author.

- Interoperability. It may be legal and necessary to reverse engineer some binary code for the purposes of interoperability. There are the famous cases of Sega vs Accolade and Atari v Nintendo, where small games companies successfully argued their right to reverse engineer some existing games, so that they could manufacture competing games for that platform. I don't know if they used decompilation for this (probably not), but it's a good example of iwhere decompilation might make a difficult job much easier.

- You can perform code checking of various kinds:

- If you have compilable code, then you can do more:

- With little user input:

- Optimise for platform. Example: you have an old program written for the 80286 processor, but you have a Pentium 4. You can recompile the code with optimisations appropriate for your actual hardware.

- Port cross platform (where the same libraries are available). For example, you have an Intel Windows version of a program, but you have an Alpha (running Windows NT). You can recompile the decompiled output with an Alpha compiler. Or recompile it with Winelib (to provide Windows libraries) and run the "Windows" program natively on your PPC laptop under Linux. Or compile it under Darwine on your Mac running OS/X. If the vendor doesn't provide one, a 64-bit driver (required for 64-bit Windows XP) might be rewritten from the decompilation of a 32-bit driver. Decompiling or disassembling an existing driver binary may be the only way to find interoperability information, e.g. to write a Linux driver.

- If you put enough effort into the decompilation to produce maintainable code, you can also:

- Fix bugs (without the tediom of patching the binary file).

- You can also add new features that were not in the original program.

- You can recover lost or unusable source code. It is estimated that 5% of all software in the world has at least some source files missing. You can use the decompiled code to replace the missing source file(s). You can also maintain code that was written in assembler, or in a language for which the compilers no longer exist.

- With little user input:

- Defeating copy protection, where the company who wrote the software (that you paid for) is out of business, and you can't transfer it to a new machine. It does happen!

- Support for programs that ship without debugging information, often linking with third party code, and one day it just stops working. Recompiling with debugging support turned on may or may not show the fault. People experience this problem in the field all the time, and at present the tools they have to work with are inadequate. Decompilation may be able to ease the support burden, even for companies that have the source code (except perhaps to some third party code).

Software Freedoms

On a SlashDot articled called "BitKeeper Love Triangle: McVoy, Linus and Tridge" 11/Apr/2005), it was posted: Copyrights on binaries (Score:4, Insightful)by Peaker (72084)

Revision: r1.17 - 29 Apr 2005 - 23:50 - MikeVanEmmerik